Venezuela’s Hyperinflation

By Neil Tamhankar and Eshan Gupta

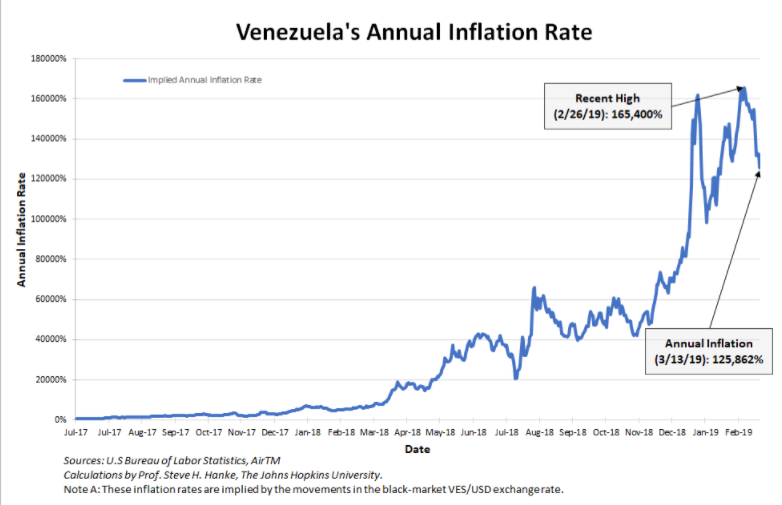

Since 2016, Venezuela’s economy has been in a state of hyperinflation, which is commonly defined as an inflation rate of more than 50% per month. Inflation occurs when an economy is overheating. Prices rise faster than wages, decreasing the purchasing power of every citizen, and the value of currency decreases. For example, if Juan has 100 bolivars, and the price of an apple is 10 bolivars, he can buy 10 apples. However, if the price of an apple increases to 20 bolivars, Juan will only be able to buy 5, decreasing his purchasing power. Venezuela’s inflation rate has reached ridiculous highs over the past few years; the rate reached 800% in 2016, 4000% in 2017, 1,700,000% in 2018, and finally an all time high of 10,000,000 percent in 2019. This means that prices for nearly every good in Venezuela have been spiraling upward for 6 years with no end in sight. The bolivar (Venezuela’s currency) has become so devalued that $1 is equal to 428,956 bolivars; compared to the exchange rate for the Mexican peso ($1 equals 20.4 pesos) the bolivar’s value has plummeted.

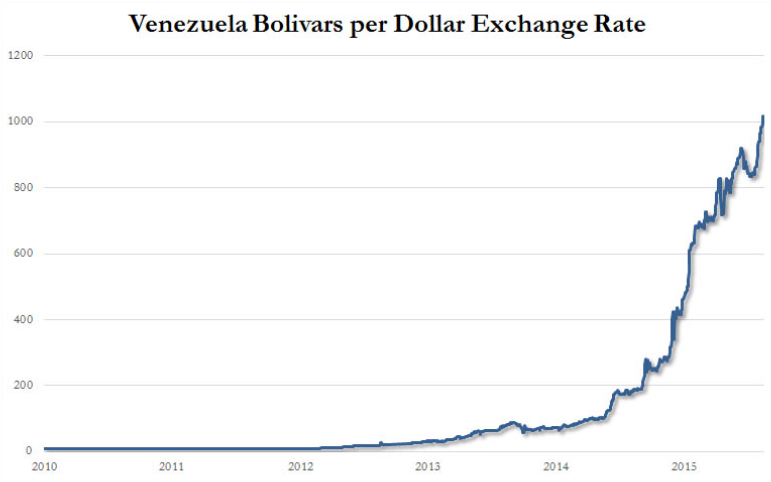

As you can see from the above chart, the bolivar has consistently lost value over time.

Venezuela’s inflation has risen to insane levels.

To put this into perspective, imagine a Venezuelan middle schooler walking home from school and deciding to stop at a convenience store for a snack. He buys a bag of chips for 10,000 bolivars and goes home to eat them. After doing his homework, he feels hungry so he goes back to the store to buy another bag of chips. When he sees the price tag, he is astonished to see that the price has increased to 15,000 bolivars due to inflation (this is an exaggeration, but close to the reality). He leaves, going home hungry.

How Did They Get Here?

While Venezuela’s hyperinflation troubles began in 2016, their history with inflation starts 3 decades earlier. In the 1980s, world oil prices dropped due to a large surplus in oil supplies. This is because when there is more supply, the value (or price) of a good decreases. For example, if an apple vendor sells only 3 apples, but there are 6 consumers, the consumers will pay higher prices to get the apples. However, if the vendor sells 6 apples, the consumers will pay less since there are enough apples for everyone. Getting back to the real world: Venezuela has massive oil reserves and was a major oil producer, and the massive loss of revenue from the lower oil prices triggered an economic collapse. The collapse caused widespread unemployment, and businesses were forced to raise their prices to stay in business, causing inflation. The leader of Venezuela at the time, President Pérez, decreased government spending. He hoped that lowering spending would slow down the economy, decreasing inflation. Decreasing government spending leads to less jobs (for example, less infrastructure/public works projects decreases the number of jobs), lower wages (workers have to accept lower wages since they are desperate for jobs), lower spending in the economy (from lower wages), lower profits for businesses, and generally a slower economy. The result is stable prices, which defeat inflation (a concept known as price level stability). Thousands lost their jobs, but the measures worked and the inflation cooled down. However, inflation did not stay down for long. In the mid-90s, Venezuela’s inflation rate averaged about 60% annually and inflation continued to worsen (for contrast, U.S.’s annual inflation rate averages about 2-3%). The resurgence in inflation is attributed to the 1994 banking crisis. In 1994, a bunch of Venezuela’s largest banks failed (essentially they lost a lot of money), forcing the government to bail them out. The closing of banks led to many Venezuelans losing their savings that were held in banks and more economic turmoil.

The country officially entered hyperinflation in December of 2016 when the monthly inflation rate for December was greater than 50% (the U.S. inflation rate at the same time was around 2%). In contrast with the inflation of the 80s, the more recent hyperinflation has been attributed to deficit spending (when the government takes loans to spend money because they are in debt) and massive amounts of money printing by the Venezuelan government to pay their debts. Increasing the supply of money will decrease its value and lead to higher prices, or as in Venezuela’s case, extremely high prices. Here’s another way to think about it: if there are $1000 circulating in a mini-economy (meaning the total amount of money everyone has in the economy is $1000), the price of all the apples in an economy is $100. If the government prints another $500, bringing the total amount in circulation to $1500, the price of the apples will increase (while wages stay the same) to match the new total value of the economy, thereby causing high inflation. The deficit spending, combined with heavy money-printing, majorly contributed to the hyperinflation that seized Venezuela in 2016.

An oil shortage also contributed to Venezuela’s inflation. How can an oil-rich country like Venezuela have an oil shortage? The country had a lot of crude oil in reserves but its refineries fell by the wayside. Underinvestment, flawed management, and a lack of maintenance led to many refineries producing less output than they used to. The lack of working, optimal refineries led to much less crude oil being refined into usable oil, driving oil prices higher and adding to inflation.

Effects of Hyperinflation

Venezuela’s hyperinflation has been particularly critical because of one area of goods whose prices have shot up: food. The leap in food prices has caused massive food shortages, with about 1 in 3 Venezuelans lacking reliable food sources. In comparison, inflation in the U.S has caused goods like gas, cars, and other commodities to become more expensive, but the situation clearly could be a lot worse. This goes to show that command economies like Venezuela, where the government regulates economic activity by controlling businesses and setting prices, tend to be more hard hit by economic afflictions than free market economies like the U.S.

While food prices (along with the price of every other good) have risen in Venezuela, the value of the bolivar has dropped. The erosion of the currency and rise in prices has caused grocery stores to establish strict measures for the previously simple task of selling groceries to Venezuelans. The stores typically ration goods because of massive shortages and require IDs from shoppers. Additionally, shoppers need to protect themselves from thieves who will try to steal their food. Also, inflation has eaten into Venezuelans’ savings. Think about parents who have been saving for medical expenses and college tuition. The family of Matthew, a native Venezuelan school goer, has saved 30,000,000 bolivars for some major expenses for Matthew. But once this inflation hits, all Matthew’s family can buy is a meal for a month with this money – this money cannot buy them a house or a college education or even medicare anymore!

A Solution

The Venezuelan government should immediately enact aggressive contractionary policy to suppress inflation. Contractionary policy falls under two buckets: fiscal and monetary. Contractionary fiscal policy includes actions like reducing government spending (therefore pumping less money into the economy) and raising taxes, which decreases the amount of money Venezuelans have. This may sound like a detriment, but with higher taxes, Venezuelans would be spending less, slowing down the economy and lowering inflation. Contractionary monetary policy mainly means raising interest rates, like the Fed is currently doing. Higher interest rates leads to less business owners taking loans to invest in their businesses and less consumers taking loans to buy goods. This is because higher interest rates make loans more expensive, leading to less demand for loans. Reduction in spending and business investment both slow down the economy because less money is in circulation and being spent, lowering inflation. Contractionary policy is not a perfect solution. Extreme contractionary policy, which is necessary with such levels of hyperinflation, will almost certainly cause a recession. There is definitely a tradeoff between inflation and recession; the key is finding a good balance.

Recap

Inflation in Venezuela has risen to astonishing levels, devastating the country’s economy and destroying the faith of the Venezuelan public in its government. The bolivar has become extremely devalued, and prices of Venezuelan goods have risen to extreme highs. In particular, food prices have risen so much that a significant portion of the population no longer has steady access to food, igniting a humanitarian crisis. In addition, the inflation destroyed Venezuelans’ savings, forcing most citizens into financial ruin. The crisis can be solved using strict, effective contractionary policy that consists of increased taxes, reduced government spending, higher interest rates, or all of them together. There is no telling when inflation in Venezuela will end, but hopefully government policies will get the job done.